Ruth Hannah Wiener was born on 4 August 1927 in Berlin, the eldest daughter of Dr. Margarethe Minna Wiener (née Saulmann) and Dr. Alfred Wiener. Ruth had an older brother, Carl, and two younger sisters, Eva Elise (born in 1930) and Mirjam Emma (born in 1933). Carl died in 1928, shortly after Ruth was born.

Ruth’s father and mother were staunch anti-Nazis: Alfred Wiener worked for the Centralverein deutshcer Staatsburger judischen Glaubens (the Central Association for German Citizens of the Jewish Faith), an organisation which attempted to combat antisemitism, and Margarethe Wiener was an economist, whose published work scrutinised the Nazis’ economic programme.

Due to the nature of their work, the Wieners foresaw the danger following the Nazis’ rise to power earlier than most and in the autumn of 1933 the family emigrated to Amsterdam, Holland. Ruth later reflected nostalgically on this relatively peaceful period, where she developed a lifelong love for Holland and the Dutch people. By 1939, Alfred Wiener knew that it was only a matter of time before Holland became unsafe for both his family and his work and he began to make arrangements to move his work to London, which he achieved shortly before war broke out in 1939. Unfortunately, the visas for Margarethe, Ruth, Eva and Mirjam did not arrive in time. On 1 September 1939 Germany invaded Poland and the Second World War commenced, leaving Ruth, her mother and two sisters trapped in Holland.

On 10 May 1940, Germany invaded and occupied Holland. New Nazi segregation laws soon affected Ruth. She had to attend a new Jewish school, she could no longer play outdoor sports, and she had to wear a yellow star. On the morning of 20 June 1943, Margarethe, Ruth, Eva and Mirjam were detained by the Nazis and sent to Westerbork, a transit camp in the south of Holland. In January 1944, after seven months in Westerbork, the family were deported to Bergen-Belsen , where conditions were considerably worse than at Westerbork.

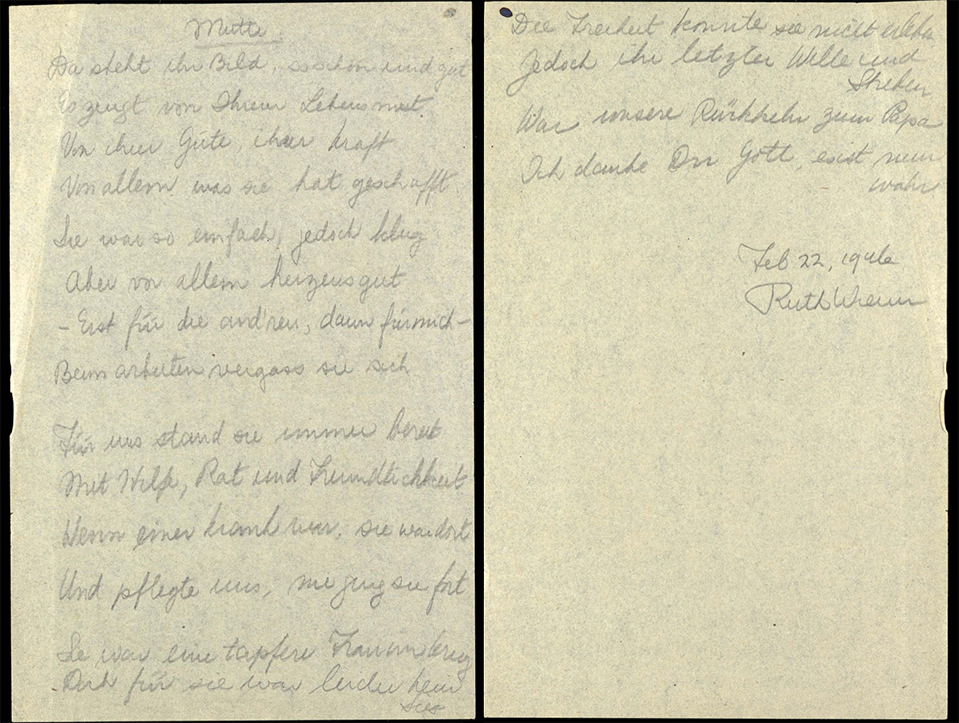

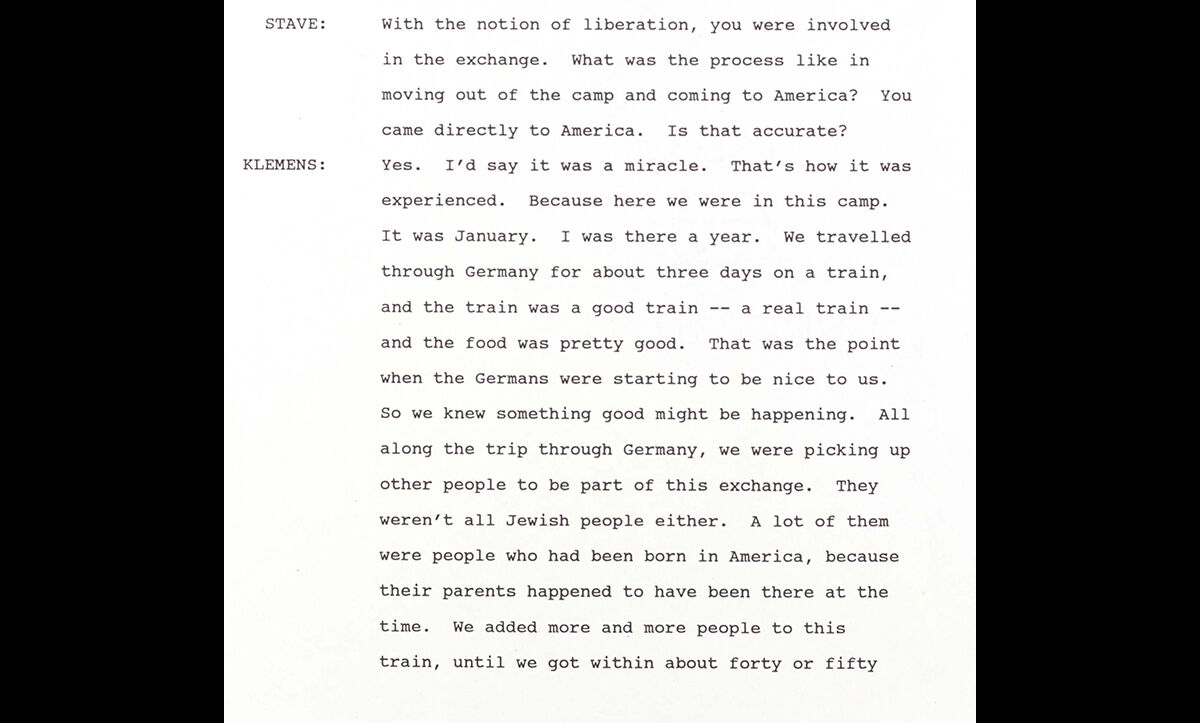

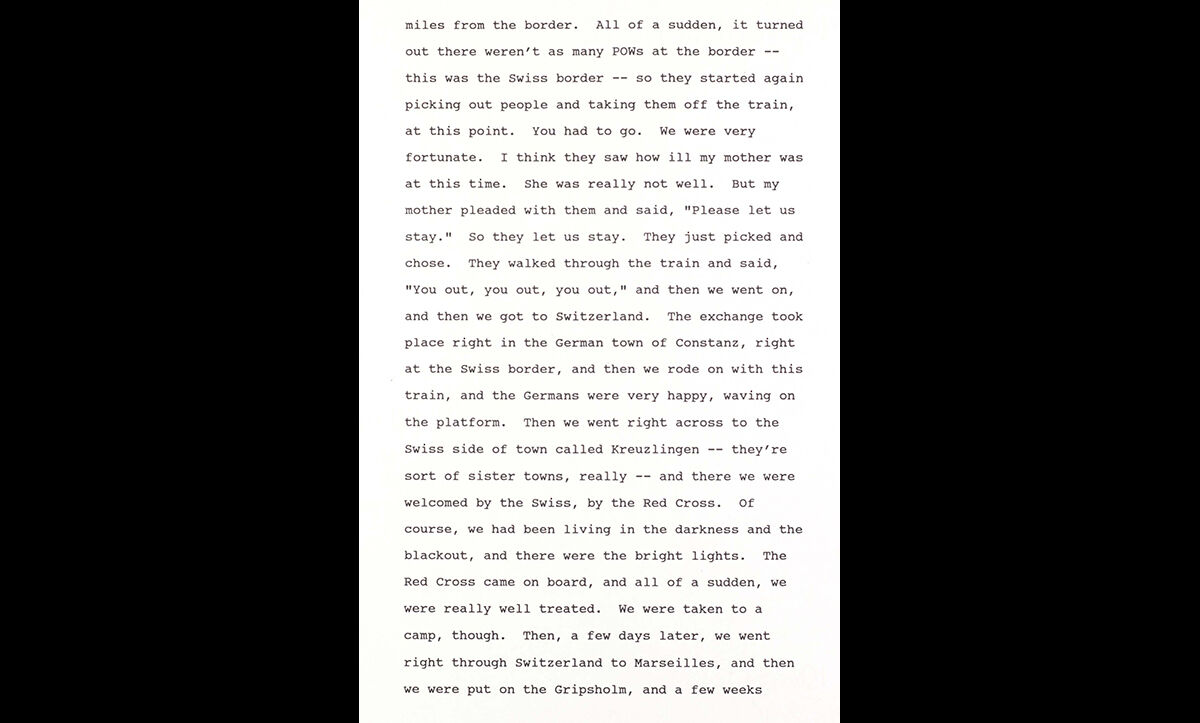

In January 1945, a rare opportunity to be on a prisoner exchange scheme and the family were released. Over the course of the year that the family were imprisoned in Bergen-Belsen, Margarethe’s health had steadily deteriorated, and she collapsed shortly after boarding a train out of Bergen-Belsen. After crossing the border to freedom into Switzerland, Margarethe was too ill to continue travelling and on 25 January 1945, she was taken to a hospital where she died. Only Ruth was permitted to attend her burial.

Shortly after their mother’s death, the sisters departed Switzerland, travelled through the south of France, and eventually made their way onto a Red Cross ship bound for New York City. In New York, after almost six years apart, the girls were reunited with their father.

Ruth and her sisters stayed in the US for another eighteen months whilst their father returned to England to work and prepare for the family to be reunited. Ruth remained in New York, living with a Jewish family, and her sisters went to live in New Hampshire with a Quaker family. In 1947, the three sisters left the US and re-joined their father in Golders Green in north London.

In London, Ruth continued her education and studied for a Batchelor of Arts degree in Foreign Languages at Birkbeck College, where she graduated in 1950. During this time, she also met and married her husband, Paul Klemens, a physicist. In 1951, Ruth and Paul emigrated to Australia, before settling in the US in 1959. In the US, Ruth continued to study, and undertook a Master of Arts degree in Education at the University of Connecticut. She then became a foreign languages teacher, starting a career which spanned 25 years. Alongside teaching, Ruth felt that it was of paramount importance to speak about the Holocaust, and she gave regular talks to schools and universities about her experiences. On 29 October 2011, Ruth died at the age of 84. Her husband, Paul, passed away the following year.